A Digital History Project

During an exceptionally frigid December in 1933, picketers faced intimidation and numerous threats as they protested on Pennsylvania Avenue in West Baltimore. Battling brutal weather conditions, they also endured harassment from police, hostility from store managers, and the unsettling presence of unfamiliar, shady onlookers. The intentions of these unidentified spectators were presumed to be sinister and troublesome to the movement, including potential violence to eliminate the boycott leader, Prophet K. Costonie. Mrs. Vivian-Thurgood Marshall recounted how one such suspicious man followed her from her home on Druid Hill Avenue as she attended a Housewives League meeting about the boycott.

Despite these menaces, the mission and commitment remained clear; disrupt the flow of pedestrian traffic into the stores that had refused to hire black workers. Over 200 young men and women committed to picketing and boycotting several establishments on Pennsylvania Avenue, determined to compel store managers and owners to hire Black clerks. The protestors and organizers stood firm in “their” community and ensured that they had their own reinforcement. Neighbors parked along the curb, allowing picketers to take respite from the cold in their car, while eateries along Pennsylvania Avenue provided sandwiches and beverages to picketers. Some local Black physicians and drug stores committed to providing care to picketers suffering from prolonged exposure to the cold, and bodyguards worked discreetly to protect their leader. Despite the community backing, the movement was curtailed just weeks later. An all-white, all-male business association on Pennsylvania Avenue successfully secured an injunction, forcing the organizers to end the picketing.

Pennsylvania Avenue, a key commercial strip in Baltimore, represented the complexity and contradictions within segregated neighborhoods in urban America. As the economic hub and pulse of the neighborhood, it was lined with white-owned businesses, including popular five-and-dime stores, that relied on predominantly Black patronage but refused to hire Black workers.

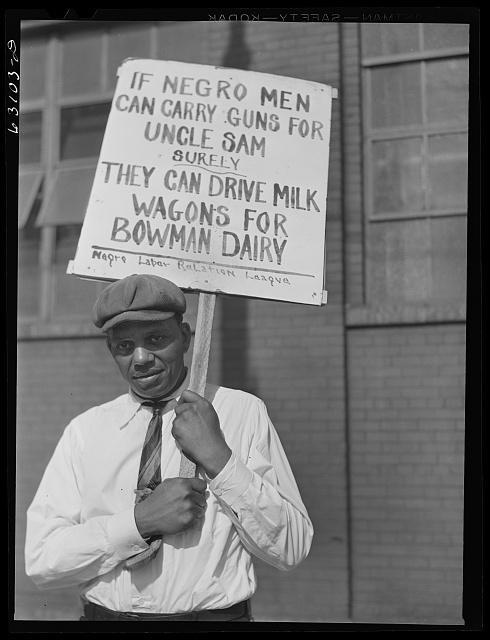

In cities across the U.S., commercial streets in segregated Black neighborhoods became sites of racial tension and power. Black communities fought for control over their own spaces, while white business owners tried to maintain dominance ( racial hierarchy). These streets became battlegrounds, where white shop owners held hiring and political power, while Black residents organized to use their collective buying power as a form of protest. The “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work” campaign was one of the first battles in this struggle, laying the groundwork for broader fights for economic and social justice.

The Movement

Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work

As approximately more than a million African Americans migrated to the urban North and Midwest in search of better opportunities, they encountered discriminatory practices, residential segregation, and limited economic opportunities. In their “new” neighborhoods, Blacks were frequently hired only for menial work such as elevator operator or janitor, or were altogether excluded from employment in the retail businesses such as shops, department stores, and grocery stores. The Great Depression exacerbated economic and social inequalities as African Americans were the first to be fired and displaced from their positions for white workers. Although Black nationalism encouraged patronage of Black-owned businesses and notions of a self-sustaining Black economy, this was not a reality during the 1920s and 1930s. An estimated 70-80 % of businesses, and up to 90% of retail businesses or shops in the segregated black neighborhoods such as Harlem, NY, Bronzeville, Chicago, and West Baltimore were white-owned. African Americans relied on white establishments for their services and local jobs.

Between 1929 and 1940, African Americans engaged in economic protests and boycotts to fight against job discrimination, and to gain control of their communities. The “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work” movement used picketing and boycotts of local businesses in segregated Black neighborhoods, to compel retail businesses to hire and retain Black workers. The job campaign and boycott movement leveraged the purchasing power of Black residents and employed strategies of disruption across dozens of American cities in the 1930s. Before an actual boycott and picketing of stores began, organizers mobilized and attempted to negotiate with store managers to hire Black workers. When no action was taken, residents took to the streets. The movement occurred in at least 30 cities/communities,1 including Chicago, Harlem, DC, Cleveland, Atlanta, and Los Angeles, and yielded tens of thousands of jobs for black residents. In total, the campaign is estimated to produce 50,000-75,000 jobs for African Americans. The largest gain from the “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work” campaign was its empowerment of African Americans to push for broader job opportunities, which, even after the movement ended, enabled them to target larger industries and companies and secure positions in sectors such as public transit, utility companies, and the defense industry

The movement reflected a diversity of supporters which included housewives, students, the Black elite, local ministers, street orators, Black newspapers, controversial cultists, and nationalists like UNIA Garveyites. It was equally opposed by and trivialized by some African American organizations, intellectuals, and newspapers. Although picketing was common in the US it was not yet widely used by African Americans because of police, threats of violence, and was perceived as disruptive and unruly. Who supported and opposed the movement varied by community and city. Overall, both support for and conflicts within the movement were the results of confining people with class, ideological, religious, and even ethnic differences (American vs Caribbean) within racially segregated spaces. The biggest threats remained to be, however, the police, the courts, store managers, business associations, and white vigilantes.

The Digital Project

A Digital Spatial Project: Mapping an Urban Protest Movement

“Mapping an Urban Protest Movement” is a digital history project that will use interactive maps to explore the “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work” movement within urban communities. It allows viewers to center specifically on the communities and corridors where these protests took place.

FOR THE INTERACTIVE MAP-click here

The map and project aims to re-center space, specifically segregated black urban space, back into the understanding and interpretation of the movement. Space is not a neutral backdrop for action, but instead reflects power and choices. “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work” has largely been seen as a movement about economics and activism ideology, but like the fights for housing equality, it is also a resistance movement about race, place, and space. Within this movement, the negotiations, boycotting, picketing, and even decisions to hire, reflect the choices and power dynamics over space. The boycott movement allowed African Americans to assert some level of autonomy, agency, and control over their space. Whether picketing businesses and retail blocks or using street corners and churches to mobilize, local residents used actions that employed visibility, community, and defiance against the businesses that imposed a racial hierarchy into the resident’s space and place.

This is an evolving project that will include more narration and details over time. This project will eventually use digital storytelling to highlight and journey through the communities within the national map and in a local community. Currently, users can view and interact with the map to see what cities organized a protest. Under each point are the city, the neighborhoods where the protest took place, active dates, and the organizing committee involved. Additional facts include the number of jobs produced by the local campaign2 and the Black population in that city. It is important, however, for me to emphasize that the “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work” campaign was never a city-wide campaign and was isolated to the segregated neighborhoods or “negro sections” of the city. The map allows viewers to zoom in directly to the communities that this movement took place in.