Planning to pursue a career in public history, I initially considered digital preservation as one potential path. However, my understanding of digital preservation is apparently a little misguided. I interpreted digital preservation as simply preserving historical items through digital means. In my understanding, this included activities such as digitizing texts, 3D models of material objects, preserving and storing audio-video files, managing digital assets, storing and backing up data, and even web archiving. I also associated it with “hoarding digital objects”, something I’m admittedly guilty of. However, after reading Trevor Owens’ The Theory and Craft of Digital Preservation, I began to grasp what digital preservation is not, though its exact definition remained hard to pin down. This reminded me of the similar challenges in defining digital humanities.

The first thing I realized is that the examples above represent methods for saving or conserving digital materials, but by themselves, do not constitute digital preservation. An essential principle emphasized in Owens’ text and our class discussions is that digital preservation is an ongoing, proactive, and strategic practice. It often requires collaborative approaches and institutional-level resources. Owens states that specialized digital preservation tools and software are “just as likely to get in the way of solving your digital preservation problems.” In other words, there is no specific “magic” digital tool that can handle preservation. Digital preservation ironically is profoundly human work that requires intentionality, continuous effort, and active thought. It begins at the building stages of a digital history project and demands selectivity. We must decide what is worth preserving and sustaining versus what can remain ephemeral.

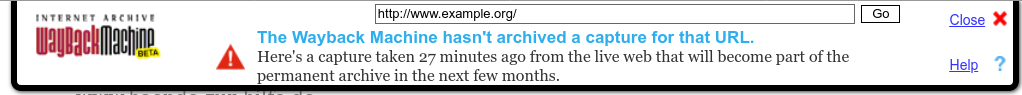

Another important takeaway is that digital preservation is not away merely about storage, it is about ensuring that materials remain “discoverable and accessible.” So the flattened HTML files of a website stored on a hard drive at the bottom of a box, hidden in multiple storage cubes in my living room with no access for researchers or the public, are not truly preserved.

Returning to the idea of being selective. Annabelle noted in class, this requires us to behave somewhat as archivists, of the digital history world. I cannot help but reflect on the heavy responsibility of digital preservation. As we discussed in class, this requires us to consider more about the political, cultural, and artistic implications of sharing and preserving our digital work. In some ways, we may unintentionally create silences or erasures while also enabling discoveries and amplifying certain narratives. It serves as another reason to apply an extra critical lens to our work, not considering the use today but that of future audiences. What are the implications of preserving and sustaining materials for several more years, versus the potential consequences of focusing only on short-term accessibility and relevance?

Hi Asha,

Thank you for the blog. I have to admit I misunderstood digital preservation similarly. I agree with what you mentioned in your blog that digital preservation is “an ongoing, proactive, and strategic practice.” Like what we discussed in class, knowing your audience will help you decide how much sustainability you need!

One of our office\’s programs is to host a virtual celebration each Fall, encouraging GMU undergrads to present their research videos. The videos have been archived and are accessible on our website. The class discussion made me think about the importance of preserving these materials and making them accessible! Students may point to these videos when applying for grad school or jobs. The earliest videos are from the event in Summer 2021. Moving forward, as we will upload more videos, I wonder what strategies we need to apply to make the website as accessible as we wish.

Hi Asha!

I really think that you highlighting the “discoverable and accessible\” part of preservation is probably one of the most important aspects of digitization as it\’s often overlooked by people (me included)! Just because you have something saved in your own personal drive does not mean it adds to this idea of digital preservation in its entirety. I think this discussion relates back to our first class meeting when we discussed how digitization needed to keep up with technology like transferring files from floppy discs to USB drives to even perhaps the cloud in order to stay relevant.

I really enjoyed your post. It highlighted a lot of things we need to be actively conscious of when venturing into the online space.

Hi Asha,

Your statement that digital preservation is \”profoundly human work that requires intentionality, continuous effort, and active thought\” really hits this week on the head. I am guilty of assuming that things online can all be preserved eternally, and I was raised believing that if you put something on the internet, it will be there forever. But your blog really highlights what our discussions and readings illuminated for me – preserving things online is highly intentional and selective. I agree that these choices are not made lightly in terms of how they affect future audiences and historical study, especially with the increasing amount of digital media and ongoing projects.

Your blog has once again deepened my understanding of digital preservation. Digital preservation is not just about the methods of saving digital materials but is an ongoing, proactive, and strategic practice. It\’s about ensuring that digital content remains discoverable and accessible over time, which requires intentional planning, continuous effort, and often, collaboration at an institutional level. Owens emphasizes that there\’s no \”magic\” tool for preservation; instead, it\’s profoundly human work that begins at the very inception of a digital project.

At the same time, having a critical perspective is really important for us, as our projects are ultimately aimed at the audience. Perhaps some of our language or designs may indirectly or directly influence the audience\’s thinking. Indeed, we should approach digital preservation with a sense of ethics and reverence.