In 2017, I was fortunate to embark on a remarkable trip to Africa, which included stops in Senegal, Morocco, and Ethiopia. Amidst the hustle and bustle of international travel and grappling with a language barrier (French in Morocco), I felt a sense of relief as I checked into my hotel room and switched on the television. On the screen was a familiar sound: Kool & the Gang performing at a Cuban music festival! Kool and the Gang, the iconic R&B band that are now 2024 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Inductees, reached their commercial peak during my childhood. The concert being re-televised on Morocco TV was a historic free concert performed in 2009 in Havana, Cuba.

With “Celebration” and Ladies Night” playing in the background, the scene held a deeper significance. Here I was, in Morocco, witnessing an American group light up a Cuban stage. Three countries, three languages, and even a history of diplomatic tension – yet, united by the universal language and experience of music. The idea that music, particularly Black music, could bridge divides and transcend borders, was not a unique revelation. The extraordinary concert, documented by the press worldwide (US, Europe, and South America), resembled US state-sponsored jazz tours from the 1950s to the 1970s. During the Cold War, the U.S. State Department established international jazz tours as a form of cultural diplomacy. These tours aimed to showcase American society’s dynamism and creativity and foster positive perceptions of the U.S. on the world stage.

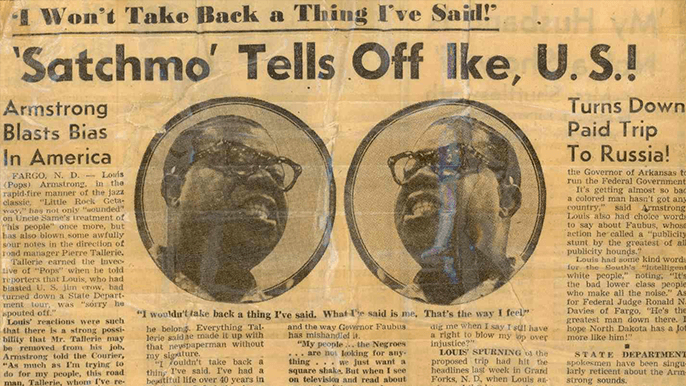

Penny Von Eschen’s book, Satchmo Blows Up the World, explores the crucial role of jazz musicians as cultural ambassadors during the Cold War and beyond. Specifically, music tours, much like the concert I watched on TV, served as a tool for advancing connections and understanding across cultural and political divides. Von Eschen argues that Jazz musicians became symbols and voices in the struggle for freedom for both civil rights at home and democracy abroad. Beyond diplomacy, these international tours also fostered connections and mutual appreciation among African Americans, Africans, and Afro-Caribbeans, united in their resistance against the oppressive forces of Jim Crow and colonialism. Overall, the musicians were driven and inspired by a desire for unity and understanding among fans and brothers across seas. Echoing this sentiment, Kool & the Gang’s leader, Robert “Kool” Bell, summed up his band’s participation in the Cuban concert by saying:

“We are all about the music. We travel the world, and our message is love, understanding and unity.”

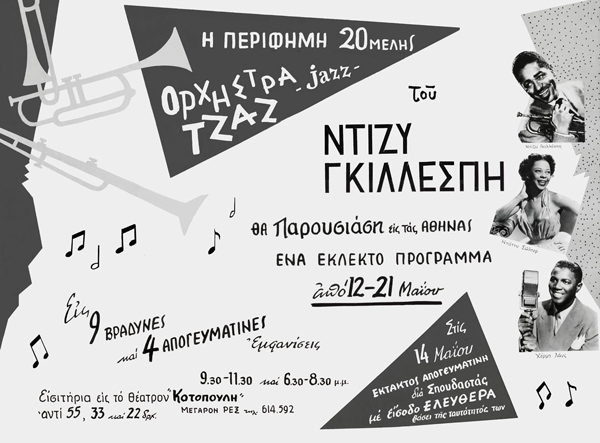

In her book, Von Eschen argues that Jazz, characterized by creative freedom, nonconformity, and improvisation, represented resistance and freedom. As such, Jazz musicians were perfect symbols to be thrown into the collision of the Cold War, the Civil Rights movement, and global decolonization between the 1950s and 1960s. The meta-narrative is that Jazz and Jazz musicians as cultural ambassadors are the peacemakers in the saga of ongoing national and international conflicts. Von Eschen guides readers on a journey with African American artists Dizzy Gillespie, Duke Ellington, and Louis Armstrong and their vocal advocacy for civil rights and democracy while on tour. In addition to intersecting the conflicts of American civil rights, global resistance against colonialism, and the Western world’s power struggle (Cold War), the book’s inclusion of coups, civil wars, internal band conflicts, debates on tradition over modernity in Jazz reflects that conflict is an overarching theme. Jazz doesn’t necessarily stop conflict, coups, or invasions but acts more as a diversionary stage, both literal and symbolic. Just as my encounter with a familiar American band in a Moroccan hotel room provided a momentary respite from the challenges of travel, so too can jazz offer a welcome escape for citizens caught in times of global tension and uncertainty.

Even in 2009, long after the Cold War had ended, the Berlin Wall had fallen, and the rise of social media and streaming had transformed music access, the impact and diplomatic significance of international jazz (and now R&B) festivals continued to be considerable. The Cuban concert arrangement was coordinated by the president of the International Foundation of the African-American Music Association, and approved as part of an experimental renewed cultural exchange between Cuba and the US during the Obama administration. The band played notably at the open-air Anti-imperialist Plaza, which sits in front of the U.S. Interests Office. Despite any diplomatic intentions and motives of Cuban or American leaders, the band insisted that “we don’t come as politicians, we come as musicians.”

Though global history and diplomacy aren’t my usual areas of study, I’m captivated by the way different cultures and groups interact within a shared space, and how these interactions shape their understanding. The idea of International music festivals and performances as a defined space that facilitates peace and understanding is worth further exploration.

Sources

Penny M. Von Eschen, Satchmo Blows up the World: Jazz Ambassadors Play the Cold War, 1st Harvard University Press paperback edition (Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England: Harvard University Press, 2006).

Rutgers University of Jazz Studies and Meridian International Center: Art for Cultural Diplomacy, “Jam Session: American Jazz Ambassadors Embrace the World”, accessed May 14, 2024, https://www.meridian.org/jazzambassadors/.

Louis Armstrong House Museum, “Louis Armstrong Archives: Digital Collections and Biography.,” accessed May 14, 2024, https://collections.louisarmstronghouse.org/.

“Kool & the Gang Gives Rare US Concert in Havana,” Saratogian (blog), December 21, 2009, https://www.saratogian.com/2009/12/21/kool-the-gang-gives-rare-us-concert-in-havana/.

ACN Agency Cuban News, “Kool & the Gang Sing in Havana,” People’s World (blog), December 22, 2009, https://www.peoplesworld.org/article/kool-the-gang-sing-in-havana/.

“Cubans Get Down on It with Kool & the Gang,” BBC News, December 21, 2009, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/8424125.stm.