As early as the 1920s, both Washington, D.C. and Harlem included a residential section known by the same name. Both sections were characterized by beautiful multi-story brick row homes and those homes matched the dignity and opulence of their residents. Both areas were constructed in the late 1800s in the backdrop of an expanding city. They would represent not only areas of architectural significance but also of social and historic significance. Being the home of early Black middle and upper class, both sections would eventually be designated as historic districts associated with the African American community. And although there were two, the name Strivers implied a certain level of exclusiveness. Strivers’ Row in Harlem, NY and Strivers’ Section in DC were corridors that housed African American exceptionalism.

The section that occupies the area between 138th and 139th street and 7th and 8th avenues in Harlem, NY is known as Strivers Row, later designated as St. Nicholas Historic district by the landmark preservation council of NYC. The Strivers’ Section Historic District in DC is located between 16th and 19th Streets, and T Street and Florida Avenue in northwest Washington. The meaning of Striver is “to exert much effort or strenuous effort toward a goal, or to struggle or fight forcefully”. It became a colloquial term in the 1920’s for Blacks striving for more, but with some negative overtone within the African American community as it referenced those trying “to live above or beyond their race”. To strive wasn’t just to aspire for more but implied distancing oneself from the predominant Negro class, and therefore it is apt that the term Strivers referenced a physical location of a community.

Objectively speaking, it was a fitting term. Both DC and Harlem were locations of migration and most African Americans in Harlem and DC were renters/boarders who did not have the money to buy property. Most African Americans worked in service or unskilled labor and were kept at lower wage than their white counterparts. At the time that the homes that would occupy Strivers’ row were built, more than 90% of Negroes were “employed as servants, porters, waiters, waitresses, teamsters, dressmakers’ laundresses, janitors and other laborers” according to Gilbert Osofsky’s Harlem: The Making of a Ghetto. Reaffirming the effort needed to buy homes in DC, author William Henry Jones in his work on DC housing, states in the 1920’s “ The negroes of Washington make strenuous efforts to secure their own homes, owing partly to the difficulties of renting desirable places and to the insecurity of tenure renting implies”. The small percentage of middle upper class in Harlem or DC, including the strivers, were either professionals, entertainers or successful businessmen. In Harlem, Strivers’ main professional occupant was the Black physician who would serve the community in their home or in the recently desegregated Harlem Hospital a few blocks away. True Harlemites referred to that section of 138th street (among others) as “Doctor’s Row”, in reference to the community of black doctors and practices that once lined the block, especially between 1930’s-1970. Their proximity and services were essential in a segregated world before the advent of the community health center movement. Similarly, the proximity of Howard University would drive professors to DC Strivers’ section. There was one major difference that distinguished the two sections. The Strivers’ section in DC was often mixed and partially surrounded by predominantly White areas. This is contrary to Striver’s Row in Harlem, where it was centered in a predominantly black neighborhood.

Harlem’s Strivers’ Row affluence centered in the ghetto, mirrored more accurately the complexity and often ambiguity of upper middle class in the African American community. Wallace Thurman described Strivers row as “the most aristocratic street in Harlem”, Yet they were never fully separated from the physical and social burdens on African Americans. A striver could never fully “status” themselves out of the African American community. Just to get to and from home, whether walking or using a streetcar, a striver would come across the alleyways, the dirt, the music, the chatter and the scene of Harlem, and symbolically Black society. In Harlem the difference between the striver and the survivor was less conspicuous, they were detached and together at the same time. As a long-term resident and heir to Harlem, I attest that both the survivor and striver may have different circles and attend different events, they also both visited similar churches, café’s, libraries and more.

Also, strivers didn’t just put in more effort than survivors, they often had an earlier advantage. Social class stratification and class distinction among African Americans started in the antebellum era and was a consequence of the social divide between an enslaved person and a free person of color. Freedom status was dependent on more factors than effort alone, including location, skills learned during enslavement, mixed ancestry, and family ties. In 1850s -1860s DC and Maryland had the highest percentage of free black populations, as cities like Baltimore and surrounding areas had reduced need for slave labor. Mississippi, Alabama, and Texas had the lowest percentage. With early freedom came access to education, paid labor, and social capital denied to other Blacks. Although free Blacks were active in advocating for the freedom for others, more often their work resulted in the freedom or elevation of close family members and individual success. Emancipation was not the great equalizer; the class difference would last through generations, most prominently in places like DC and New Orleans. Those who had early skill sets or advanced education (before grade school was even compulsory) would become the first middle class.

Strivers’ row and Strivers section was not designed for the affluent African Americans that would occupy their space, but it was defined by them. As the population grew in the 19th century, in Manhattan and Washington DC, the cities expanded upward. Both Harlem and U street section of DC, started as underdeveloped areas constructed to act as a residential suburb of the greater city area for White elites. The elevated railroad line in New York and street cars in DC that extended upward further facilitated their growth. The spark that attracted affluent African Americans slightly differed between Harlem and DC.

Harlem

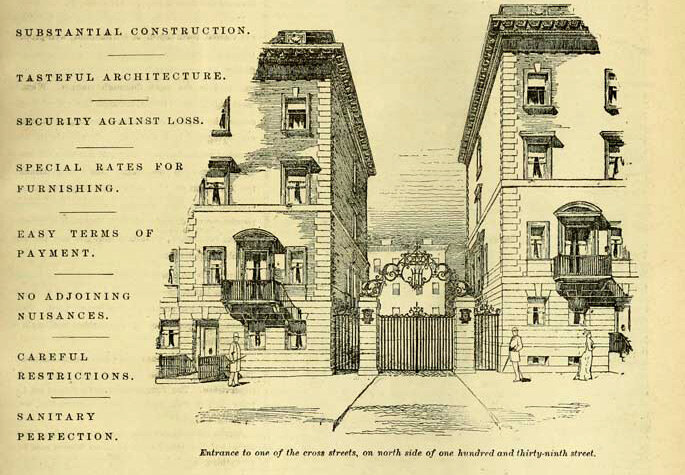

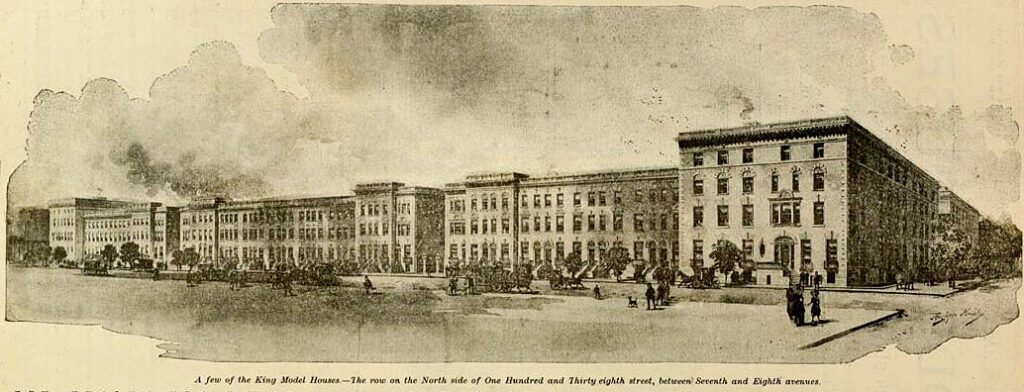

In the late 1800’s, there was a spurt of speculation, construction and development in Harlem expecting to attract the new (richer) masses. In 1891, New York builder, David H. King Jr. acquired a tract of land on West 138th and West 139th Streets between Seventh and Eighth Avenues. King was known to have a hand in the building of the Statue of Liberty’s pedestal, the Washington Arch in Washington Square Park, and the original Madison Square Garden. He commissioned three prominent New York architectural firms to build 4 rows of houses, which would become the unique combination of Georgian and Italian renaissance inspired luxurious brownstones standing today, the D.H. King Houses.

Ironically the boom that led to the construction of homes for the wealthy white elite facilitated the movement of Blacks into Harlem. Harlem had more homes to supply than demand. Real estate speculators moved to Harlem to make a profit by purchasing new property and reselling or renting at exorbitant prices to make profit. In the setting of a financial panic of 1893, rents were too high and “precluded any great rush to West Harlem ” as described by Gilbert Osofsky’s. The homes sat vacant and unused for more than a decade. Blacks and Italians had already lived on the periphery, underdeveloped areas of Harlem. Over time realtors recommended selling to the “Negroes, migrating into the city in the early 1900’s from the South and Caribbean. More and more white New Yorkers abandoned Harlem and more blacks moved in. (Of note, although New York had a free black population in the 19th century, during and after slavery was abolished in NY state, Blacks had a high mortality rate and infant mortality rate compared to all other ethnic groups. The formerly enslaved population and their descendants was very small in NYC by the time Harlem was developed, and the majority of residents would be migrants )

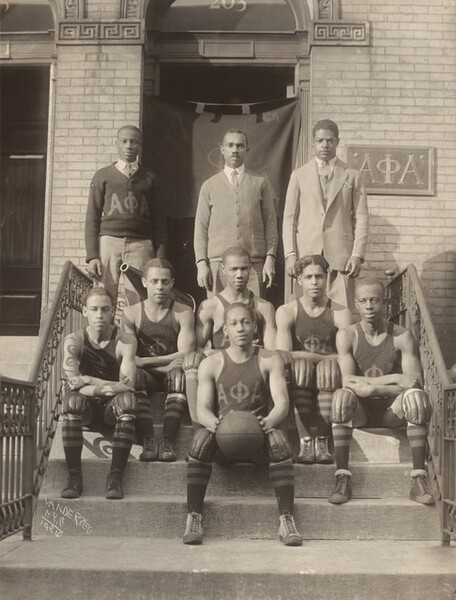

The houses on 138th and 139th, known as the D. H. King houses were made available to African Americans around 1920 and prominent African American upper class started moving to the area. The rule of segregation and housing discrimination did not distinguish wealthy or professional African Americans from poor Blacks. All occupations and classes African Americans were eventually limited to the certain areas of the city, namely parts of Brooklyn and Harlem. Those who had a little more could choose the better paved streets and newer constructed homes. Strivers row as it would be called starting in the 1930’s would attract the Black, elite, professionals, and entertainers. Some well-known residents include W. C. Handy, the father of jazz, musician, and composer Eubie Blake, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, Congressman and preacher Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. William Pickens, a former Dean and Vice-President of Morgan College (now Morgan State). The NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission charter highlights the most prominent Harlem doctors who have lived there including L. T. Wright, brain surgeon and Surgical Director of Harlem Hospital from 1938-52, P. M. Murray, Dean and Professor of Surgery at Howard University (1917-1918) and Paul Collins, a staff member in the Eye Clinic of Harlem Hospital.

Washington D.C.

Similar to the development of Harlem, the area that would include the Strivers’ section in Washington D.C., first developed from the need for expansion of the city center. African Americans first started residing in the northern borders as part of contraband camps during the Civil War. These camps were later relocated and disbanded, but the foundation of the African American community had been established. Freedman’s Hospital was founded in 1862 to provide medical treatment of former slaves, and Howard University, an institution that developed from the Bureau of Freedmen, Refugees and Abandoned Lands (the Freedmen’s Bureau), would become a fixture in the area. Like Harlem, the area underwent speculative development. The area evolved to include residents of mixed working-class and professional, Black and White. As the area developed more, because of proximity to Howard University and transportation, the Black middle class and elites, largely professors and business owners, moved into the stretch that would become Strivers’ section. One of the early residents was abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who lived in the area and purchased homes on 17th and U Streets in 1877. John Aubrey Davis, the brainchild behind DC New Negro alliance. For the most part, to the east, U Street between 7th and 17th Streets would be a thriving black entertainment business area with residential, while Dupont Circle to the south and west remained an almost exclusively white neighborhood.

Both Harlem and DC would be affected by urban decay in the 1960’s through 1980’s. The reason or arguments as to why to be discussed in future posts. In Harlem with each passing year more of Harlem elites moved out. With other residents not able to afford purchasing homes, some of the King houses were converted first to boarding houses or later for SRO use. Fortunately, the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission designated the area as a historic district and landmark, the St. Nicholas Historic District in 1967, and the neighborhood was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1975. Through preservation and renovations, the area retains its glamor and beauty. The historic designation is used (or exploited) by real estate agencies as a selling point, almost mimicking the attention that created them the first time. Similarly, the Strivers’ Section Historic District was added to the District of Columbia Inventory of Historic Sites on June 30, 1983, and listed on the National Register of Historic Places on February 6, 1985. Gentrification has had a displacing effect on the African American communities of DC and Harlem. However, Harlem still retains a strong African American presence and culture, with the Schomburg Center for Black Culture, Harlem Hospital, and black businesses within walking distance. The Strivers Section Historic District is no longer predominantly African American; the district is designated into Ward 2, which only reports that 8 % African American, but lies somewhat close to the black institutions and demographics of Ward 1. The U Street corridor has been largely gentrified, with scattered black owned businesses in place.

Strivers’ Section Historic District, District of Columbia Office of Planning