In “Beyond Freedom’s Reach,” Adam Rothman recounts the story of Rosa Herera, a mother who sought the return of her children who were kidnapped by her former enslavers. In an effort to hold on to their “property” during the occupation by the Union in New Orleans during the Civil War, the DeHart’s family seized Rosa Herera’s children and relocated to Cuba, while she was imprisoned. The case made its way through the courts, a complicated and divided system during the Reconstruction Era, before mother and children would be reunited.

Rothman book opens by emphasizing the deliberate and consistent disruption of family ties and erasure of identity for enslaved individuals through legal, physical and emotional means. In addition to repeated forced separation and migration, there was omission of identity and familial relationship in name and written records (census, migration papers, bills of sale, baptismal papers etc). In highlighting this, the author expresses how important yet challenging the reunification for black families can be.

“In fact, one crucial piece of information that is missing from all the records of Rose’s life is the identity of her father. The erasure of biological paternity was a hallmark, almost a necessity, of slaveholders’ claim to wield paternal authority over slaves.“1

The book underscores that the disruption of family, community, and ancestral ties among Black Americans extended beyond the Middle Passage. Enslaved men, women, and children were separated, sold off, and scattered across the country through the domestic slave trade. Family members were separate and sold to resolve debts, due to the death of plantation owner, or to merely instill order, control, or punishment.

Separation also occurred as individuals left the South and their extended families to seek freedom, escape threats of racial violence, or pursue job opportunities in the North following emancipation. Systemic racism would continue to divide families through punitive practices and policies such mass incarceration, excessive child separation and overzealous protective services. 100 years post-civil -war hundreds of established black communities, towns were uprooted, destroyed or displaced due to a pattern of mob violence, eminent domain, urban renewal and disinvestment. The African American story has been ravished by separation of family, home and identity.

Reunification and Rediscovery

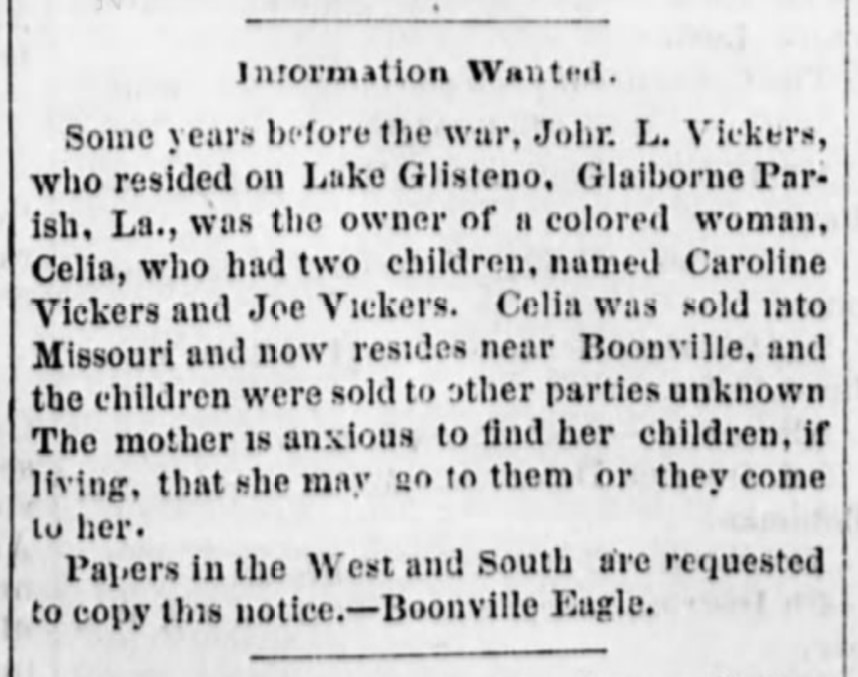

A mother (Celia) searching for her children Caroline Vickers and Joe Vickers,” The State Journal (Jefferson City, MO), May 26, 1876, Last Seen: Finding Family After Slavery, accessed September 10, 2023, https://informationwanted.org/items/show/1467

The protagonist Rose Herrara is not an exception, reunification was a major goal of formerly enslaved Blacks after the civil war. Last Seen: Finding Family After Slavery is a project by the Zinn Education Project that has collected, archived, and shared thousands of “Information Wanted” ads on their digital platform. These ads were placed by recently emancipated individuals seeking to reunite with lost family and friends who were separated during slavery. When we grasp the profound extent of separation that African Americans endured, the significance of researching, reconnecting, and bridging these historical gaps can be truly appreciated.

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library. (1864). Wm. Kinnegy returning to the Union Army with his family, from whom he had been separated by slavery for five years Retrieved from https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47df-9578-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

The quest to reconnect with lost family members is a universal and the 21st century has ushered in a new era of family and history exploration. . Genealogy websites, DNA testing services like Ancestry DNA, digitized historical archives, and the power of social media have revolutionized how we reconnect with our past and scattered ancestors. The culmination of these online and digital tools creates the unique ability to research one’s family’s roots and ancestry in a way like never before. While all backgrounds and ethnicities benefit from the impact of the digital revolution on genealogy, it poses a unique opportunity for African Americans, who throughout American history were repeatedly isolated from their families, communities and home.

The digital-social revolution created the perfect conditions for what I like to refer to as the Rediscovery Renaissance, the renewed interest or revival in family research and history almost as an art form, a tangible, spiritual and mental bridge to get everything back. There is an authentic joy, curiosity, and excitement in doing their genealogy, family trees, history, and reunions. During this time more African American Historical and Genealogical Societies have organized and chartered, with the purpose of highlighting local history and providing useful tools for family genealogy. A few dozen African American genealogy groups now exist on Facebook. There has been emergence of or renovation/ restoration of historic homes, (many through county, state or national parks commissions) including the Carter G. Woodson Home National Historic Site and the Josiah Henson in Montgomery County which clarifies the origins of Uncle Tom in Harriet Beecher Stowe novel. The Rediscovery Renaissance gives agency to African Americans to not just identify the names or location of our ancestors or connect with distant descendants but to understand the unique history, heritage, and culture of where their family come from and how that reflects today. It recognizes the culturally rich regional history of all of us within America, from creole culture of New Orleans to the culture of the Mississippi Delta, to movements that emerged as result of the Great Migration. It involves oral history from family members’ experience during Jim Crow or finding WWII draft papers for great uncles and grandparents and celebrating their service to this country. It is understanding the contributions, but recognizing the injustices that forced our families to move to the big city in the first place.

Rediscovery Renaissance, the renewed interest or revival in family research and history almost as an art form, a tangible, spiritual and mental bridge to get everything back. There is an authentic joy, curiosity, and excitement in doing their genealogy, family trees, history, and reunions.

The role of public and digital history

One cannot minimize the role of public history in both the traditional museum and digital forms in this renaissance. Relatively new museums include the Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African American History and Culture in Baltimore city ( 2005), The National Museum of African American History of Culture (NMAAHC) in DC ( 2016), the Whitney Plantation in Louisiana (2014), and the International African American Museum in Charleston, S.C. (2023), play a pivot role in reconnecting visitors with the past. Black Americans can now access records from the National Archives, state archives or local libraries and research centers of their ancestors from the convenience of their home, instead of some 1000 mile trip to visit a local heritage site. The Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) heritage and culture has digitized, uploaded and enabled a search portal of millions of pages of Freedmen’s Bureau Records. The collections at the Louisiana Digital library and Schomburg Center of Black Culture digital are also noteworthy examples. Hundreds of thousands of records have been digitized and opened to the public by local, regional and state institutions that include maps, photographs, oral history and historic documents largely through institutional collaboration. Historians and universities have produced targeted projects and digital storytelling initiatives to explore historical questions and events tied to specific locations. Noteworthy examples include Race and Place, An African American community in Jim crow South: Charlottesville, Virginia and Revisiting and Revisualizing Syracuse’s 15th Ward.

This rediscovery is closely intertwined with the recent African American literary movement, which highlights the history of institutional racism and contemporary race relations and includes the works of Ta-Nehisi Coates, Ibram X. Kendi and Nikole Hannah-Jones- author of the 1619 project. Of course, no movement of African Americans comes without attempts at suppression. Currently multiple states and school board have outright manipulated or suppressed Black history curriculums and AP African Studies. However, the awakening is already here. History accessibility is a crucial tool and friend to African Americans and the rediscovery renaissance is laying to rest the idea of not knowing our past. It is the ghost of Rose Herrara’s quest that we all have inside of us.

- Adam Rothman, Beyond Freedom’s Reach : A Kidnapping in the Twilight of Slavery (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2015), 12. ↩︎